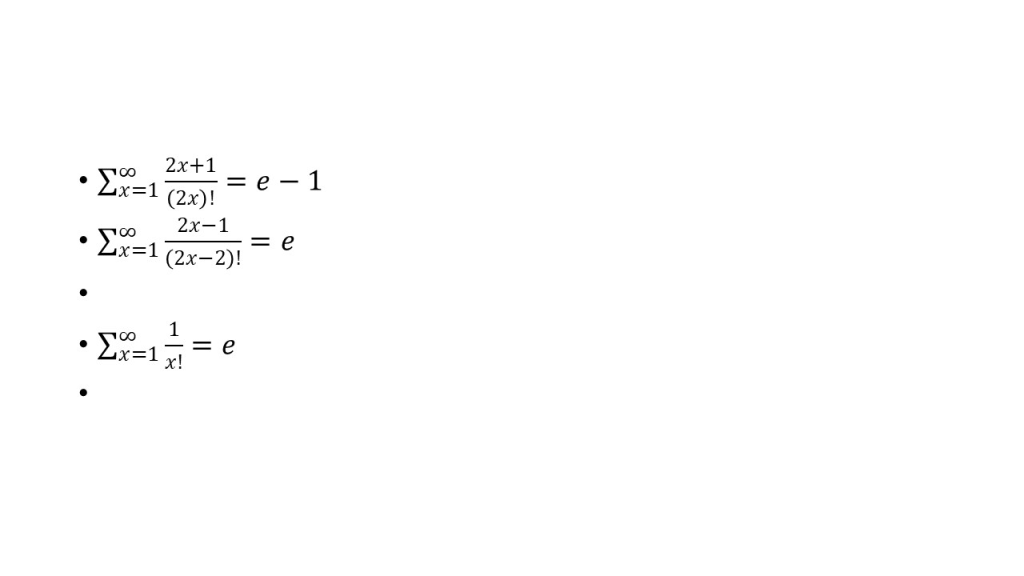

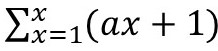

The first two series for e are of my own innovation are far faster than Newton’s method below giving 12+ digits after 7 terms compared to 15+ terms for Newton’s series.

Nunghead

The first two series for e are of my own innovation are far faster than Newton’s method below giving 12+ digits after 7 terms compared to 15+ terms for Newton’s series.

Nunghead

This criterion is based on Wilson’s Theorem.

Recall that Wilson’s Theorem states that a number (x) is prime if and only if (x-1)!+1)/x is an integer.

The generalization for twin primes goes like this If x is the lesser member of a twin prime pair then

(x-1)!+1)/x and (x-1)!+1)/(x+2) are both integers therefore the denominators are a twin prime pair.

Thank you,

Nungheaf

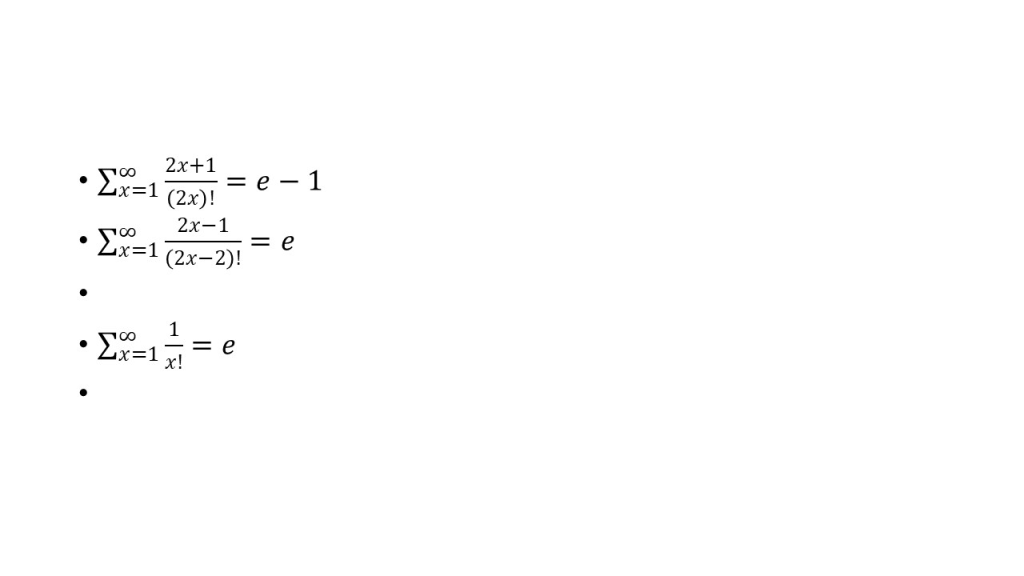

A formula for iterating the nth polygonal number is below. In the formula below a is herewith denoted to be greater than zero. For A=1 one gets the triangular numbers, a=2 the square numbers, and so on. This formula was derived when the author observed that the triangular numbers can be represented by the sum of x numbers of the form x+1 with x>= 0. He then carried out the experiment further and discovered every polygonal number may be represented as the sum of x numbers of the form ax+1 where x is greater than or equal to zero.

Unfortunately for the author this formula of his was a rediscovery.

Links below where this formula is discussed.

http://www.maths.surrey.ac.uk/hosted-sites/R.Knott/Figurate/figurate.html#section4.1

http://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Hypsicles.html

The algorithm works like this.

First, we start with the equation x+y=z (x,y)>0

Next, we pick an input value for z. In this case we will pick z= 5.

Then, we proceed to solve the equation in terms of x.

Next, we enumerate the solutions to the equation. Namely, 4+1=5, 3+2=5, 2+3=5, and 1+4=5.

Then, check if the values of x and y in each equation are primitive i.e when x and y share no common factor.

Finally, If yes declare that 5 is prime. If not declare that 5 is composite. In this case, all solutions of z are primitive therefore z is prime.

To boil it down further z is prime if all pairs of solutions to x+y=z are primitive to each other. But if even if one pair of solutions is not primitive to each other then z is composite.

Visit this page for an interactive demo of this Primality test.

Thank you,

Nunghead

The following formula of mine is a rediscovery of the standard taylor series for the sin function. I thought to note this because of its impact on my mathematical development as an individual.

At first I had only discovered the Taylor Series of sin(1) that being (down below on the right side) where x=1 while recalling the Madhava-Leibniz series and then asking myself what would happen if I added factorials. To my utter shock and amazement the series seemed to be tending(when summed to n terms) to sin(1) (The Madhava-Leibniz series is simply the same series as sin(1) without the factorials in its denominator)

Latter, I revisited the Madhava-Leibniz series article in Wikipedia. There it states that the Madhava-Leibniz series is just a subsequence of the inverse tangent function with x=1. I then looked at the series of the inverse tangent function(Same series as Sin(x) without factorials in the denominator) and saw that if I added factorials to the denominators of the terms of this series, I would get the sin(x) series! In retrospect, all I had was a computer with the Madhava-Leibniz series article pulled up, a calculator, and a over curious mind.

See Madhava-Leibniz series article on Wikipedia-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leibniz_formula_for_%CF%80

Interestingly a nice approximation for Pi (accurate to six digits) is 11^ln(11) *10^-2 curiously enough.

Thank you,

Nunghead

Without further ado we begin.

Take a look at the sequence 0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15 ,21,…

Sum every two consecutive terms in the sequence.

What do you notice?

The sequence is the square numbers I hear you say.

And indeed they seem to be the proverbial square numbers i.e 1, 4, 9 ,16, 25, 36,… (Appears everywhere don’t you think?)

Proving this is very elementary starting with the fact that the nth triangular number is of the form x(x+1)/2 and that the (n-1)th triangular number is simply x(x-1)/2.

First,we expand both identities establishing that x(x+1)/2 is equal to(x^2+x)/2 (by the distributive property) and that x(x-1)/2 is equal to (x^2-x)/2 (by the distributive property again).

Next, we sum the the two like terms cancelling both the x and -x leaving(2x^2)/2 at the end.

Finally, we divide 2x^2 by 2 revealing x^2 at the end.

QED

Thank you,

Nunghead

PS: Did you catch that I alluded to the fact that the sum of n odd numbers is a perfect square. This is the reasoning for saying “Appears everywhere, don’t you think”.

It seems that I have rediscovered the centered polygonal numbers. Just a little announcement for all of you. This announcement refers to previous post on series of difference 2ax.

The formula for the centered polygonal numbers is A(x(x+1)/2)+1. A represents the constant multiplier between every two consecutive terms.

Thank you,

Nunghead

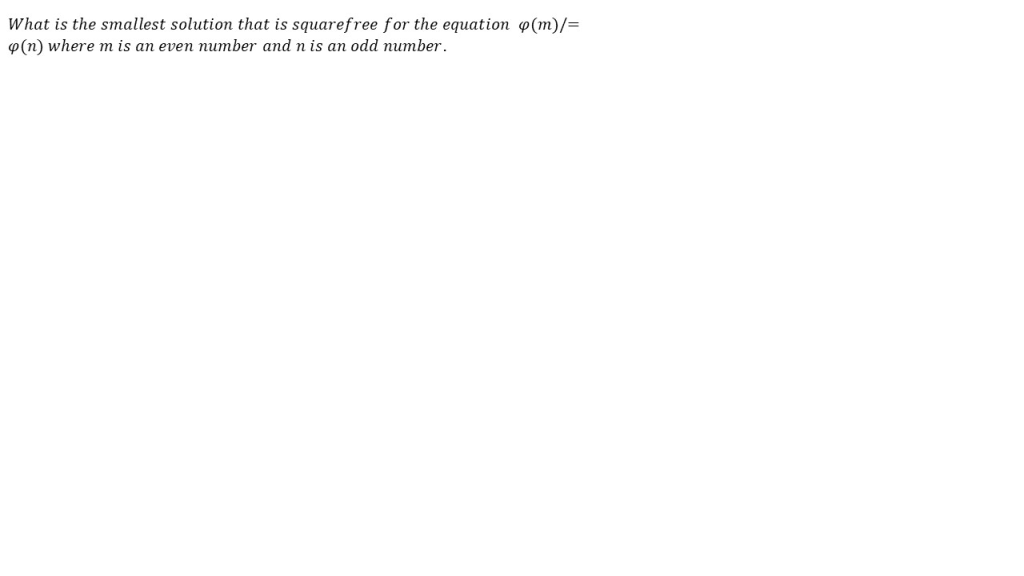

Is there a pair of prime numbers such that both n x 2^n +1 and n x 2^n -1 are prime if n is also prime? I conjecture that there is not such a pair.

As always I welcome the readers to prove or disprove this conjecture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodall_number

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cullen_number

Thank you,

Nunghead

A(x(x+1)/2))+1 where a is a even number; x is any number from 1 to infinity.

This strikingly general, simple, formula subsumes all my previous formulas for finding the rules of series like 1, 5, 13, 25,41,61, and so on… with the exception of series that do not have difference ax where a >1.

I will reference my other posts below.

Some other interesting series

Another interesting series of numbers.

An interesting series of numbers.

This formula iterates the terms of series with difference of 2Ax. Difference of Ax can be done with a being odd. To clarify suppose we have the series 1,3,7,13,21,31, and so on… , we will then assign a starting term of one firstly. Next, we will take the differences of each two terms i.e (3-1), (7-3), and so on. Then, we will find what multiple of an even number or odd number. is (in this case it is two). Now, we know the A value in my formula. Finally, just plug in any number from 1 to infinity.